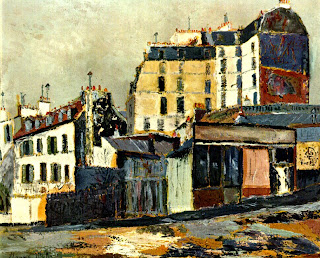

For all the beauty and vibrancy of Paris in the daytime, with nightfall, especially on nights like tonight, it can turn dark and melancholy. The streets on the hill are quiet, curving and cobblestoned. You can’t see far ahead of you, and unlike most parts of Paris, Montmartre has enough empty space to make parts of it feel like the countryside. There’s still a vineyard, windmills, a small cemetery. And there’s more. There are those who lived on the hill before us and walked these narrow streets and alleys — Modigliani, Pascin, Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, who immortalized these very streets. Maurice Utrillo grew up in Montmartre, the son of Suzanne Valadron, a famous artist in her own right. He was the neighborhood’s own bad boy, fighting, breaking street lamps, trading his paintings for cheap alcohol. Local legend says he exposed himself to strangers on the street, yelling, “I paint with this!” Who can say he doesn’t still wander here on rainy nights?

His red nylon leash is narrow and really not very strong. Not what most people would use to control a powerful 120 pound dog. But the real purpose of Bernie’s leash is to tie us together so we don’t ever lose each other. I always put the hand loop securely around my wrist so that if I should fall down — or worse, be hit by a car or have a heart attack — Bernie would remain with me instead of running loose, lost in the wilds of Paris. The reality is that Bernie is always able to choose where he wants to go and because he is so strong, I would have to follow. He is a mellow boy, though, and is usually content to let me be the leader. The leash is superfluous. Where he most likes to walk is directly behind me as if I’m blazing a trail through high brush and his life depends on putting his feet directly in my footsteps. It’s a strange quirk, a puzzle, but then many things about Bernie are puzzles.

So out we go. Down the stairs. Through the empty lobby. The lobby television is turned on from 9 to 9, for the benefit of those renting rooms for just one or two nights, since there are no televisions in the hotel rooms. There is some kind of a French game show on with the contestants in a high state of excitement. I can’t understand a word anyone says.

When I try to push open the glass door to the street, the wind slams it closed again. Lightning suddenly flashes and cracks and Bernie and I both jump.

“Well Bernie, our first storm in Paris!” I say to him in a voice that I hope sounds like “this is going to be fun” instead of “I’m scared — let’s run like hell!”

Back in the apartment, I take out one of the blue towels I bought at Les Galeries Lafayette when we first got here, and dry my own hair, and then go to work on Bernie. In just that short time, his coat is so soaked that he’s dripping on the floor.

I know it’s a rat. I have an irrational fear of rats and so of course it has to be a rat. I have a theory that rats are attracted to people who are afraid of them, just like bees are attracted to people who are allergic to bee stings. The two things go together. The rats can always find me. No matter where I live, a rat shows up. I think about rats every day. (I confess this with some embarrassment.) I listen for them and watch for them, and I see them scurrying silently, along the power lines behind all the buildings. They’re there every night from dusk until daylight. Rat sensitive people know these things. I don’t know where they hide during the day, but whoever the person was who said you’re always within six feet of a rat, did me no favor. I now am unable to control constant reconnaissance sweeps and surveillance to anticipate where a rat might be hiding within a six foot radius. In the wall? Behind the sofa? Under the bed?

When I was a little girl, I was mesmerized by my Grandpa’s story of what happened to him as a young man on his Ohio farm: he was in the barn and a rat ran straight up his pants leg. I spent my childhood on the alert for random rats that might be coming my way.

In the late 60s, my husband and I left California for about three years, and rented a three acre farm property outside of Indianapolis, Indiana. We saw it as our part in the back-to-the-land movement of the 60s and early 70s. Our house was surrounded by neighbor’s corn and soybean fields. We parked our car in the barn. We grew crops of fragrant sweet peas that climbed the wooden barnyard fence and sweet tomatoes warmed by the sun. We got the kids a pony and raced up and down our road on an old Cushman Scooter we called “Hi Baby.” We listened to Ravi Shankar albums and wore love beads and painted big orange flowers on our mailbox out by the road. We made dandelion wine using a recipe from the Whole Earth Catalogue and the dandelions from our front yard.

Every fall, the day of the first cold snap when we knew summer was over, the field mice came in the house to get warm. We could hear them scurrying on the floor above our heads as we laid in bed. Our brand new baby girl was up there. Our 4 and 6 year-olds were up there. I was in a constant state of mouse alarm. The mice were outside. The mice were inside. The mice were upstairs. The mice were downstairs. The mice were everywhere. I stood at the kitchen sink washing dishes and had a field mouse run over my bare feet. Fall was always my favorite season, and now I dreaded it.

The barn where we parked the car had rats in it. Lots of rats. Big rats that took off in all directions along the rafters when you opened the barn door. Big rats that could run right up your pants leg.

I recently developed a small vitreous separation in my left eye, which has left me with a black area in my sight, in the vague shape of a cobweb. But to me it doesn’t look like a cobweb. It constantly takes me by surprise. It looks like a rat, running just where I can catch a glimpse of it out of the corner of my eye.

Now the sound of something rustling in the kitchen — which we all know is a rat — freezes me. Bernie has the opposite reaction. He runs into the dark kitchen and begins to sniff with a loud, snuffling noise that I’ve never heard him make before. He snuffs between the stove and refrigerator. He snuffs under the sink. He snuffs right into the living room, following along the baseboard all the way to the bookcase.

It’s a bad night. Bernie spends most of it in the middle of the floor on alert. I spend most of it cowering in my bed, watching Bernie and being ever-so-careful not to let a foot or hand hang over the side of the mattress in case it would be suddenly brushed by something furry.

The next morning, I see Pierre in the lobby. I breathlessly tell him about our night. He’s much more blase about it than I would like. Instead of being appropriately alarmed and assuring me that he will somehow come to my rescue, he tells me about the chasse aux rats also known as le smash, which takes place in Paris every May and June. City employees check cellars and buildings for rats. The baby rats are born in spring and if not found by the rat hunters, one pair could produce 5,000 more rats. The chasse aux rats usually comes to our street, he assures me.

I think I need poison. Where could I get it? How much would it take? Where do the poisoned bodies go? Seriously. Do they run out to the alleys or gutters to die or do they go to the middle of your kitchen? And what about Bernie? If I poison this rat and then Bernie gets the rat, obviously that would in turn poison him too. What about a trap? But then if I set a trap, I would have to wait to hear it click and then hope the trap actually killed the rat instead of just catching a foot or something so I would have to do something creative with both the trap and the rat. Both alternatives make me too nervous so I don’t do anything. And sooner than I would like, the sun begins to set and it’s dusk again. The dreaded wake-up time.

OK, it is…yes, it is a rat. Bernie runs back into the living room and looks at me up on the table. Out of his mouth sticks a long, hairless rat tail. My hysterical reaction alarms him, and he drops it. A seriously wounded giant rat, now sluggishly staggers and sways and lurches around the room.

At least Bernie and I can sleep that night. No rustling sounds, no rats, no

I’m going to have to kill it. The question is how. Neither rat trap nor poison are of any use to me now. Anything violent is out. I just don’t have the nerve for it. No hitting it over the head with a hammer, for example. Way too squishy. Painless is also preferable. And I certainly can’t do anything that means I have to touch it. So we have eliminated all of the obvious ways that immediately come to mind.

Of course the rat is still there. It has even advanced toward the front door, and is now struggling to get up the bottom step. Using all the meager emotional reserves I have left, I do a fast rat-into-plastic-scoop and close the lid. Really, really tight. Back into the trash it goes.

Back in the apartment, anxiety has me in a tight grip. It’s over, I tell myself. But I keep thinking that I can hear the rat downstairs digging at the sides of its plastic coffin, trying to escape. One more time, I think. I’ll just check to make sure it’s dead. Of course it isn’t. We need to take it someplace away from us where it’s not in the throes of dying right under our window. That’s too close and creepy, and I know I’ll compulsively need to check it all night long. We put the rat/coffin in a brown bag and head out.

If I were a rat, an icky, dirty rat with long sharp teeth and the ability to run right up your leg, where would I want to be left to die? Well, first, I’m sure it wouldn’t be in a plastic left-over lasagna container. Bernie and I walk slowly, in the general direction of the Place de Tertre, furtively peeking down alleys. I’m gingerly holding the bag and it’s contents, fighting the willies. We can both hear the still not dead rat scratching against the sides of the container. Bernie puts his nose against the bag and makes that snuffling noise.

A scene worthy of Dostoevsky: Bernie, the perpetrator. I can’t bring myself to say murderer. That’s too harsh. And besides, the rat is not really dead yet. Just dying. Me, the willing, even eager, accomplice. And the rat? The victim. Should I say innocent?

We stop at a large dumpster outside of an old building. I hesitate. It seems so impersonal. Then we spot a small, beat up metal trashcan at the outer edge of a grassy yard. Better, but not perfect. I still hesitate. The rat, which is growing in size and aggression in my mind by the minute, continues to claw at the smooth sides of the plastic. It is really beginning to get on my nerves. Maybe there isn’t such a thing as a perfect place to die. Maybe the damn thing will just have to live with our decision. So to speak.

I remove the trash can lid as quietly as possible and drop the bag holding the rat inside the homemade coffin. Down it goes. Down, down, down until it hits the bottom of the metal can. Plop. Bernie and I turn and walk away.